The Route of Lost Kingdoms stretches from inside the gates of the Kruger National Park at the ancient stone wall site of Thulamela, follows a trail of myths and legends to the Mapungubwe World Heritage site and onwards to the small town of Alldays. The route gives tourists the opportunity to explore this undiscovered region in the north of South Africa, bordering Botswana and Zimbabwe.

Thulamela is a stone walled site situated in the Far North region of the Kruger Park and dates back approximately 450–500 years. This late Iron Age site forms part of what is called the Zimbabwe culture, which is believed to have started at Mapungubwe.

Thulamela:

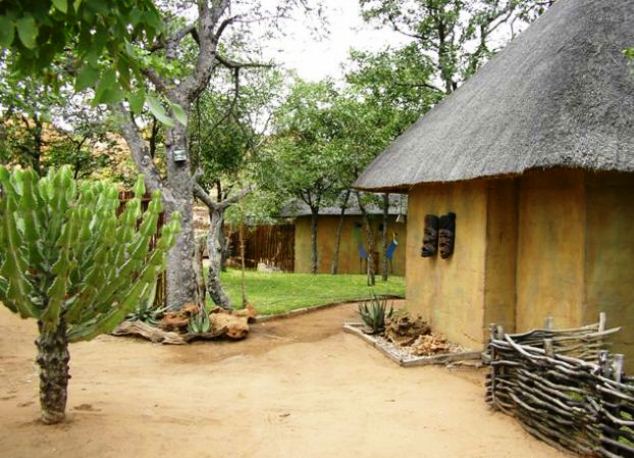

Thulamela is a Venda word, meaning ‘place of birth‘. The site consists of stone ruins of the royal citadel and dates back to between the 15th and 17th centuries. According to oral histories, the Nyai division of the Shona – speaking Lembethu occupied Thulamela and believed that there was a mystical relationship between their leader and the land. They believed that the ancestors of the leader (or Khosi) would intercede on behalf of the nation. The Khosi, who was an elusive figure and could only be seen by certain individuals, lived in a secluded hilltop palace in view of the commoners as an indication of his sacredness.

The Khosi had a number of officials working for him, some of the most important included:

The Messenger – a close and trusted confidant who kept the chief informed of all court proceedings and visitors;

Personal Diviner and Herbalist – safeguarded the Chief’s health and scrutinized the intention of the visitors;

Makhadzi (ritual sister) – the chief ruled together with her. Her function was that of national advisor and had to be kept informed of all decisions taken by the council. She was also instrumental in the appointment of a new chief;

Khotsimunene (brother) – legal expert in charge of the public court.

If a commoner wished to meet the Khosi he would go to a special chamber with two entrances (one from the Khosi’s hut which he would use and the other for the visitor). The chamber was divided probably by a central wall separating the visitor from the Khosi and so emphasising the Khosi’s sacredness.

Both Thulamela and Great Zimbabwe were thriving commercial cities. Commercial traders transported their goods on the Shashe and Limpopo Rivers. These waterways connected the Shona with African east coast commercial trading centres, which networked into the markets of India and China. The Shona people built hundreds of cities of stone, crowded with three story apartment complexes, housing tens of thousands of people.

Architecture was designed with curves. The round homes would nestle against the rounded outer walls in a perfect fit. In this manner, not a precious square inch of area would be lost. The walls were built from stones taken from nearby hills. Great rocks were cut using torches and then chiselled into blocks. Building blocks fitted so perfectly that mortar was not needed to hold the walls in place. The Shona used curved walls inside the city to section off living areas.

Great Zimbabwe contained eighteen thousand people. Royalty lived within the city walls, farmers and workers lived outside. A Shona home would be thirty feet across, a two to three story building, with thick walls coloured in red. Homes were packed together so they touched one another. At night, the cooking fires would create smog over the city that could be seen for miles.

One thousand years ago, Mapungubwe was the centre of the largest kingdom in the subcontinent, where a highly sophisticated people traded gold and ivory with China, India and Egypt. The Iron Age site, discovered in 1932, but hidden from public attention until only recently, has been declared a World Heritage Site by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO). Mapungubwe (meaning ‘hill of the jackal’) first attracted attention in modern times when gold beads, bangles, bowls and figurines were discovered on the summit. Since then Mapungubwe has been excavated and once again there is evidence of an extensive African farming society, based on cattle keeping with agriculture, but in this case with trade playing an increasingly important role.

Mapungubwe:

Mapungubwe hill is 300m long, broad at one end, tapering at the other. It is only accessible by means of two very steep and narrow paths that twist their way to the summit, and yet 2 000 tons of soil had been artificially transported to the very top by a prehistoric people of unknown identity. The hill is surrounded by mystery and legend. Local African legends hold the hill taboo and regard it with so much awe that they turn their backs to it at the mere mention of the name, and they believe that those who climb the hill place their lives in jeopardy.

On New Year’s Eve 1932, ESJ van Graan together with his son, three friends and a young African man, whom they had persuaded with much difficulty to guide them, ventured to the summit of the hill. Here they found the remnants of a lost and once powerful civilization. The hill was covered in ash and soil deposits among which they found iron tools, pots, copper beads and even heaps of boulders positioned so that, at a moments notice, they may be rolled down upon the heads of enemies who dared to climb the cliffs. Where the ground cover had been eroded, they found richly adorned graves … and gold. Fortunately, Van Graan’s son had studied ethnology at the University of Pretoria and, recognizing the academic value of the site; he contacted Professor Leo Fouche and so began the biggest Iron Age archaeological project ever undertaken by any southern African university, which remains an ongoing project today.

Archaeological enquiry uncovered the remnants of numerous dwellings, which had been built on the ruins of predecessors over many generations, resulting in a series of habitation phases. Radiocarbon dates show that the first buildings were erected below the hill at the beginning of the 11th century AD. But adjacent to Mapungubwe is the sister site of Bambadyanalo, which was settled even earlier. It seems that the centre of the state shifted from Bambandyanalo to Mapungubwe hill in about AD 1045, when the town most probably became overcrowded. It was also at about this time that hills and mountains became associated with royalty and the noble classes began to build their structure on high ground.

(The van Graan party discovered a gravesite, later named M1, rich with gold ornaments. A large quantity of gold wire adorned the neck and arms of the skeleton, and about 130 of these were still in relatively good condition. All in all, the amount of gold from this burial amounted to 7 503 ounces).

Although Mapungubwe has been scientifically investigated since the early 1930’s, many of its mysteries lie unanswered. It is believed that Mapungubwe was home to an advanced culture of people. The civilization thrived as a sophisticated trading centre from around 1200 to 1300 AD. It was the centre of the largest kingdom in the sub-continent, where a highly sophisticated people traded gold and ivory with China, India and Egypt. The region had a population of more than 5 000 inhabitants.

Mapungubwe is probably the earliest known site in southern Africa where evidence of a class-based society existed (Mapungubwe’s leaders were separated from the rest of the inhabitants). What is so fascinating about Mapungubwe is that it is testimony to the existence of an African civilisation that flourished before colonisation.

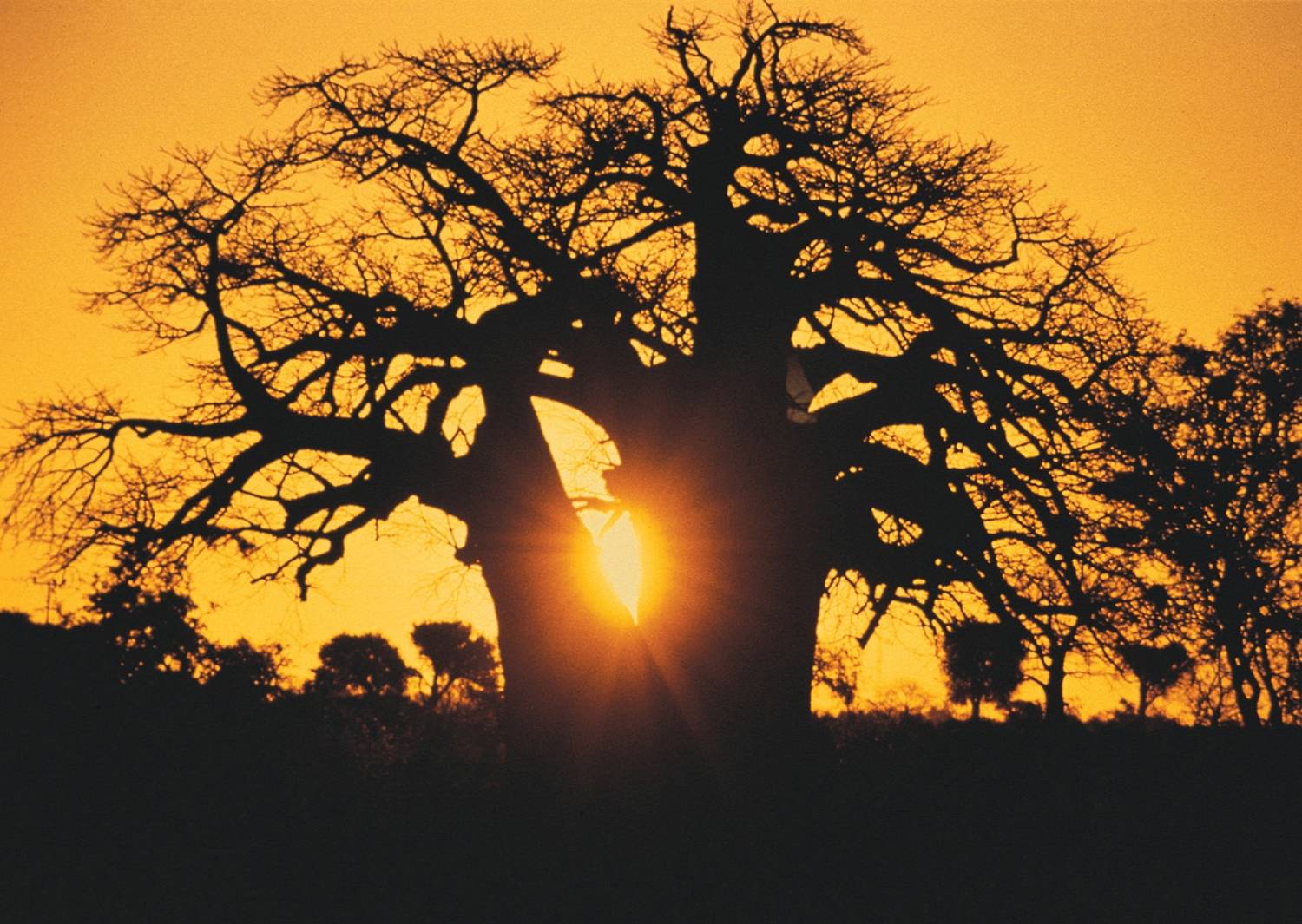

The route passes through both these ancient sites while giving tourists the opportunity to explore the lifestyles of people living in the region today. Rural life can be hard and people have adapted in many different ways to the arid bushveld environment. Take the time to visit some of the villages and meet the people of this ancient land. You will also have the opportunity to see many baobabs as they line the roads and can visit the biggest recorded baobab in the world that is believed to be approximately 3 000 years old. To get to the tree, take the most direct road to Sagole Spa and then drive west along the road that goes through Sagole Spa until you see a signboard reading ‘Big Tree’ to the right. If you get lost, just ask for directions.

The Baobab Tree:

All baobabs are deciduous trees ranging in height from 5-20m. The baobab tree (also referred to as the upside down tree) is a strange looking tree that grows in low-lying areas in Africa and Australia. It can grow to enormous sizes and carbon dating indicates that they may live to be 3 000 years old.

When bare of leaves, the spreading branches of the baobab look like roots sticking up into the air, as if it had been planted upside-down. Baobabs are very difficult to kill, they can be burnt, or stripped of their bark, and they will just form new bark and carry on growing. When they do die, they simply rot from the inside and suddenly collapse, leaving a heap of fibres, which makes many people think that they don’t die at all, but simply disappear.

An old baobab tree can create its own ecosystem, as it supports the life of countless creatures, from the largest of mammals to the thousands of tiny creatures scurrying in and out of its crevices. Birds nest in its branches; baboons devour the fruit; bush babies and fruit bats drink the nectar and pollinate the flowers, and elephants have been known to chop down and consume a whole tree.

A baby baobab tree looks very different from its adult form and this is why the Bushmen believe that it doesn’t grow like other trees, but suddenly crashes to the ground with a thump, fully grown, and then one day simply disappears. No wonder they are thought of as magical trees.

The baobab tree has large whitish flowers that open at night. The fruit, which grows up to a foot long, contains tartaric acid and vitamin C and can either be sucked, or soaked in water to make a refreshing drink.

The fruit can also be roasted and ground up to make a coffee-like drink. The fruit is not the only part of the baobab that can be used. The bark is pounded to make rope, mats, baskets, paper and cloth; the leaves can be boiled and eaten, and glue can be made from the pollen.

Fresh baobab leaves provide an edible vegetable similar to spinach, which is also used medicinally to treat kidney and bladder disease, asthma, insect bites, and several other maladies. The tasty and nutritious fruits and seeds of several species are sought after, while pollen from the African and Australian baobabs is mixed with water to make glue.

Along the Zambezi, the tribes believe that when the world was young the baobabs were upright and proud. However for some unknown reason, they lorded over the lesser growths. The gods became angry and uprooted the baobabs, thrusting them back into the ground, root upwards. Evil spirits now haunt the sweet white flowers and anyone who picks one will be killed by a lion.

One gigantic baobab in Zambia is said to be haunted by a ghostly python. Before the white man came, a large python lived in the hollow trunk and was worshipped by the local natives. When they prayed for rain, fine crops and good hunting, the python answered their prayers. The first white hunter shot the python and this event led to disastrous consequences. On still nights the natives claim to hear a continuous hissing sound from the old tree.

In addition to the people there are opportunities for good game-viewing at the Kruger National Park, The Mapungubwe National Park or many of the private game reserves in the area. The Venetia Wild Dog Project is also located on the route where tourists are given the opportunity to radio-track the Venetia wild dogs with the researchers on the project. The African wild dog, also known as the Cape hunting dog, is Africa’s most endangered carnivore.

The African wild dog:

The African wild dog is a gregarious, pack-living animal with behaviour similar to that of the well-known wolf of the northern hemisphere. The wild dog has a similar role in nature to that of the wolf in that it removes weak and unhealthy animals from the prey population. Like the wolf, the wild dog has been persecuted relentlessly.

The African wild dog is a slim, long-legged animal about the size of an Alsatian dog. Its coat is a dappled combination of tan, black and white – each individual having a unique pattern. They differ from true dogs and wolves in that they have only four, not five, toes on each foot. Their large rounded ears are characteristic and contribute to an extremely acute sense of hearing.

Wild dogs live in closely-knit packs of up to fifteen adults together with their young. Each pack has one dominant female and one dominant male. Usually only these two will mate and produce offspring. All pack members cooperate in the rearing of pups.

A high-pitched twittering, associated with excitement, is often heard when the pack is at a carcass or when they greet each other on returning from a hunt or awakening after a doze in the shade. A hooting call, called the `whoo’ call, allows the members of the pack to find one another when the pack breaks up.

Often regarded as merciless and cruel killers, wild dogs are in fact among the most efficient of Africa’s large predators. Their bad reputation is unjustified and probably a result of the frequent observation of their kills by people, as the dogs hunt mostly by day. Wild dogs hunt as a pack – they quickly single out a weak or injured animal within a herd, and the animal is then pursued until it can run no further. Wild dogs are tireless runners and chases may cover several kilometres. Contrary to popular belief, the dogs do not take turns to wear down prey. The mottled hunters quickly kill and consume their prey – impala, grey duiker, steenbok, and the young of the larger antelopes are popular items on their menu.

Wild dogs favour savanna woodland with reasonable rainfall. They occur patchily south of the Sahara, where they are now rarely found outside the borders of wildlife sanctuaries. In southern Africa, wild dogs are confined to large game reserves, such as the Kruger, Hwange, Gonarezhou, Moremi, and Chobe parks as well as the smaller Hluhluwe-Umfolozi Park. Free-roaming packs still occur in the Bushmanland region of Namibia, while their status in Mozambique is unknown.

Why endangered?

African wild dogs are great roamers and frequently come into contact with farmers and their livestock. Since they prey on small stock they are often shot or poisoned by farmers. Until the 1960’s even game rangers eliminated the dogs wherever they could: they were blamed for creating havoc amongst antelope herds, which were then regarded as the priorities of wildlife preservation.

Recent research on these interesting creatures has revealed their fascinating social habits and beneficial role in weeding weak animals out of antelope populations. Reserves now prize any packs living within their boundaries, these being the only places where wild dogs will survive. Packs often leave the boundaries of protected areas and are then at great risk from stock farmers. Although they breed well in captivity and are thus available for reintroduction, there are few suitable areas to which wild dogs can be returned.

What you can do:

Be sure to report sightings of wild dogs in the visitor’s books of national parks and game reserves. Game rangers would be particularly interested to hear of any pups or dens that you may have seen.

People interested in donating money to support African wild dog research should contact the Endangered Wildlife Trust, Private Bag X11, Parkview, 2122. Tel. +27 11 486 1102.

From Mapungubwe you can head to Pontdrift, where a crocodile farm can be visited before heading off to the small town of Alldays, a traditional hunting hotspot.

The route is ideally located as a starting point to explore the countries of Zimbabwe and Botswana.

The Beitbridge border post to Zimbabwe operates 24 hours a day and can be contacted at:

Tel: +27 15 530 0070

The Pontdrift border post into Botswana is open daily from 08:00-16:00 and can be contacted at:

Tel: +27 15 575 1561

Please be warned that the route falls within a malaria area and it is advisable to take the necessary precautions.

Thulamela Route:

This sub-route roughly stretches from the Pafuri region in the Kruger National Park to Musina. The Pafuri region lies in the northern most sector of the Kruger National Park and is located between the Limpopo and Luvuvhu Rivers. To the north and east lies Mozambique and Zimbabwe. This area is destined to become the core of a new transfrontier or ‘peace‘ park that will straddle South Africa, Mozambique and Zimbabwe and is known as the Greater Limpopo Transfrontier Park.

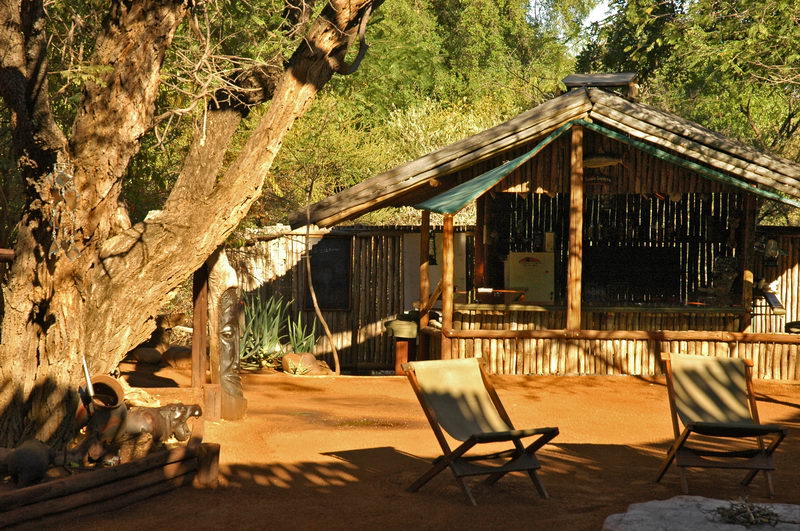

A project called the Makuleke ‘Concession’ created a trust for the Makuleke people living adjacent to the park. The reason why this Trust came into being is that the Makuleke people used to live in the area prior to 1989. They have been awarded this area back by the South African Government and the Makuleke people now own the land. The Communal Property Association (CPA) Trust represents all the Makuleke people and benefits come in the form of direct cash, training, skills transfers, jobs and community development projects that have the lodges as their direct patrons. A percentage of all the money earned by the lodges gets paid directly to the Makuleke CPA. This is a Trust that has been set up to benefit all of the Makuleke people who live in the Makuleke villages outside of the Kruger National Park.

The Makuleke’s could have moved back into the area – but have elected to stay where they are and to keep this as part of the Kruger National Park and to ensure that conservation of the area continues. The Makuleke people won their land back under the ‘new’ South African Government’s land restitution process that allows anyone that was forcibly removed off their land anytime after 1913, to claim their land back through a formal land claim process.

The Makuleke’s were one of the first tribes to get their land back in a formally protected area and they have received a lot of attention from this process, as this was viewed as a groundbreaking process that could make or break conservation in the post Apartheid South Africa.

Kruger Park and the Makuleke people have vowed to make this area a showpiece of what can be achieved when communities, formal conservation authorities and ethical private sector partners work together for the benefit of all.

On the game-viewing front, this area is famous for the large herds of Elephant and Buffalo that are resident most of the year round. They concentrate in particular around the permanent waters of the Luvuvhu River in the dry winter months. There are resident prides of Lion and the Luvuvhu riparian system supports a healthy population of Leopard.

Wild Dog and Cheetah have been sighted hunting the strong population of Nyala and Impala that live alongside the Luvuvhu system. On the eastern most boundary at ‘Crooks Corner‘ the Luvuvhu supports a large population of Hippo and Crocodile.

The Makuleke Concession is probably one of the few places in the Kruger where one has a good chance of spotting Eland and Sharpe’s Grysbok, and is regarded as probably the birding hotspot of South Africa with specialities such as Pel’s Fishing Owl, Wattle-eyed Flycatcher, Goldenbacked Pytilia, Crowned Eagles and Racket-tailed rollers. A lot of central Africa birds like the Mashona hyliota are only found in South Africa up in the Pafuri area.

One of the activities available in the area is attendance at the paleo-anthropological activities and lectures. This area could become one of the most important areas in all of Africa for paleo work. There is plenty of evidence of early man, stretching back some two million years ago right up to about 400 years ago when the Thulamela dynasty ruled in this area. The Shona people constructed walls and other structures that are not dissimilar to what is found in the Great Zimbabwe. There are rock engravings, hand tools and maybe even burial grounds.

From Pafuri the route can be followed to Musina. Musina (previously called Messina) is the northernmost town in the Limpopo Province. The town developed around the copper mining industry in the area. Copper was first discovered in prehistoric times by the Musina people who named it ‘musina’, meaning ‘spoiler‘, because they considered it a poor substitute for iron, which is what they were after. The mineral was later rediscovered and mined by 20th century miners. Today iron, coal, magnetite, graphite, asbestos, diamonds and copper are mined here. With fascinating attractions and many game farms in the area, tourism and hunting play an important role in the economy of the town. Botanical highlights of the region include fine specimens of baobab trees and impala lilies, which are both protected species. Agricultural products include citrus, mangoes, tomatoes and dates.

The Musina Museum and Library at the Civic Centre provides interesting details of the town’s social and natural history, while the original Zeederberg Mail Coach, used between Pretoria and Zimbabwe from the 1890’s, can be viewed in front of the centre. Natural wonders include the Matakwe – a single rock of bulai granite measuring 38ha in size on the Musina experimental farm off the R527 towards Pontdrift. Visits are by appointment only. In the Messina Nature Reserve, a particularly impressive baobab specimen, known as the Elephant’s Trunk because of the shape of one of its branches, can be seen in the Erich Mayer Park, named after a well-known painter of baobabs. Another park worth visiting is the Impala Lily Park. The Bulai/Dongola Execution Rocks mark the site where the Musina chiefs of old executed their prisoners. At Small Bulai on the side of the road the minor offenders were executed, while serious offenders met their fate at the large rock south of the road. The rocks are found 20km west of Musina (Messina) on the R572 towards Pontdrift.

Fishing is a popular pastime and there are many fine angling spots in the area. Adventure options in the area include hiking, 4×4 trails, white-water rafting on the Limpopo, game- and bird-watching safaris, wild dog viewing and gyrocopter flights.

*Information on Musina courtesy of www.golimpopo.com

Mapungubwe Route:

The Mapungubwe Route lies west of Musina and roughly stretches to the Pontdrift border post. This is the route to the ancient Kingdom of Mapungubwe, South Africa’s first Kingdom, which existed in the 13th century from about 1220 to 1290AD, on top of Mapungubwe Hill, the ‘place of jackals‘. It is here where gold artefacts, including the Golden Rhino and other treasures have been discovered, revealing a sophisticated civilisation that was capable of working gold and traded with the Indian Ocean trade network that included the countries of Arabia, China, Indonesia and India. Mapungubwe was the forerunner of the Great Zimbabwe civilisation, and it is estimated that up to 5000 people lived around the area known as Mapungubwe hill.

The Mapungubwe Landscape was declared a World Heritage Site on 3rd July 2003, confirming the international importance given to this area to ensure that the natural bio-diversity of the fauna and flora, as well as the African Iron Age archaeological sites are preserved for future generations to learn about and enjoy.

However, the Mapungubwe Route is not only the road to the ancient Kingdom. It is also the road to one of South Africa’s newest national parks, the Mapungubwe National Park that incorporates the World Heritage Site. The northern boundary of the Park is the Limpopo River. This once mighty river’s banks are still strewn about with giant fever trees, mashatu trees and huge sycamore figs. The view point overlooking the confluence of the Shashe and Limpopo rivers is a vista where three countries, Zimbabwe, Botswana and South Africa, meet. The area boasts an impressive landscape including sandstone cliffs, balancing rocks, riverine forests, mopane bushveld and views of the Limpopo River. The landscape changes dramatically after suitable rain and supports many endemic species of plants and flowers. The boundaries of the Mapungubwe National Park will ultimately include about 28000 hectares. The park will form the core of the proposed Limpopo-Shashe TransFrontier Conservation Area, incorporating parts of Zimbabwe, Botswana and South Africa. Wildlife at present includes elephant, giraffe, eland, gemsbok, blue wildebeest, red hartebeest, zebra, kudu, waterbuck, impala, bushbuck, klipspringer and other plains game. The park offers facilities for both overnight visitors and day visitors. There are birding and game viewing hides, elevated tree-top walks to the Limpopo River, Eco (4×4) Trails and picnic sites. Guided visits to and up onto Mapungubwe Hill, to San rock art and dinosaur fossils are available, led by SANParks guides.

The Mapungubwe Route is an area with a great diversity of bird species. It is an area of crossover covering the most southerly latitude for the northern species while being the most northerly latitude for many of the southern species. It is also an area of crossover between the desert birds of the west and the tropical birds of the east. Many of the migrations pass over this area, and vagrants are frequently spotted. In excess of 400 bird species have been identified in the area. This area is also included in The Soutpansberg Limpopo Birding Route that was developed in conjunction with Birdlife SA.

The Mapungubwe Route also provides visitors the opportunity to see a crocodile farm, San rock art, wildlife, wilderness trails and even diamonds at the De Beers Venetia diamond mine.

Along the Mapungubwe Route the Baobab Tree (Adansonia digitata) is the undisputed king of the bush. These giant trees with their enormous girth and dominating presence are surrounded by legend, one of which explains the root-like branches by saying that the gods, in a frivolous mood, planted the tree upside down, exposing the roots. There is a nature reserve in the area that was established some years ago to preserve the baobabs in the area and over a hundred mature specimens of this fascinating tree can be seen. This small reserve also contains the world’s oldest exposed datable rock, a piece of granite gneiss with an estimated age of 3852 million years. It is a good place to see the impressive and majestic sable antelope.

A Baobab Trail wends its way amongst many baobabs, most over 1000 years old. Each of these baobabs has its own character and a name describing it. It is a one or two day walking trail, but it is also possible to follow the route on a mountain bike.

Scattered along the Mapungubwe Route, impressive Rock Figs grow out of huge rocks while some of their roots flow over the rock surface.

Alldays Route:

Alldays, and the villages of Vivo and Dendron, serve an extensive area of private game and hunting farms. Prolific game – including the Big Five, accommodation and good hunting facilities attract many domestic and international trophy hunters.

Being a traditional hunting area, there are three taxidermists that operate in the area. Citrus farming on the banks of the Limpopo River is also an important economic activity in the district. Several giant trees that occur in and around Alldays are another noteworthy feature of the district. A baobab at Bakleikraal – 21m in circumference, a wild fig in Alldays – bigger than the famous Wonder Tree in Pretoria and a Nyala tree that covers a surface of 100 square metres, are of particular interest. The Venetia Diamond Mine close by is one of De Beers’ six diamond mining operations in South Africa and the only major diamond mine to be developed in South Africa in the last 25 years. Opened by former De Beers chairman, the late Harry Oppenheimer in 1992, the mine represents one of De Beers’ biggest single investments in South Africa and is the country’s largest producer of diamonds. Visits to the mine must be arranged in advance.

Historical treasures in the area include San rock art at Mapungubwe, Little Muck and Kaoxa Bush Camp, as well as remnants of the first ferry (‘pont’) used by elephant hunters to cross the Limpopo. Today at the Pontdrift border post between Botswana and South Africa, visitors are elevated in carts and taken over the river to view elephants and other game. Visits can also be arranged to the salt pans close by that attracted hundreds of elephants from Botswana in the past. At the Ratho and Parma Crocodile Farms on the Limpopo River some 60km from Alldays, close on 4 000 crocodiles can be seen, while at Bandur Safaris lions kept in captivity can be viewed. The Ghompi Game Reserve in the vicinity of Alldays is also worth a visit.